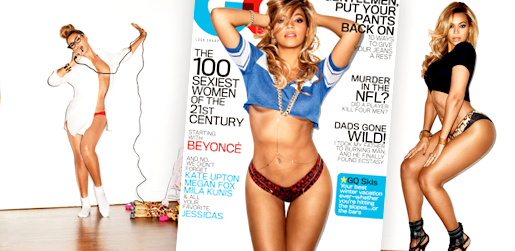

Beyoncé is ready to receive you now. From the chair where she’s sitting, in the conference room of her sleek office suite in midtown Manhattan, at a round table elegantly laden with fine china, crisp cloth napkins, and take-out sushi from Nobu, she could toss some edamame over her shoulder and hit her sixteen Grammys, each wall-mounted in its own Plexiglas box. She is luminous, with that perfect smile and smooth coffee skin that shines under a blondish topknot and bangs. Today she’s showing none of the bodaciously thick, hush-your-mouth body that’s on display onstage, in her videos, and on these pages. This is Business Beyoncé, hypercomposed Beyoncé—fashionable, elegant, in charge. She’s wearing the handiwork of no fewer than seven designers, among them Givenchy (the golden pin at her neck), Day Birger et Mikkelsen (her dainty gray-pink petal-collar blouse), Christian Louboutin (her pink five-inch studded heels), and Isabel Marant (her floral pants). She does not get up—a video camera has already been aimed at her face and turned on—so you greet her as you sit down. You have an agreed-upon window of time. Maybe a little more, if she finds you amusing.

You’re here to talk about her big post-baby comeback (Blue Ivy, her daughter with Jay-Z, is a year old), which Beyoncé is marking in classic Beyoncé fashion: with a Hydra-headed pop-cultural blitzkrieg. This month, two weeks after she headlines the halftime show at Super Bowl XLVII, she will premiere an HBO “documentary”—more like a visual autobiography—about herself and her family that she financed, directed, produced, narrated, and stars in. This is a woman, after all, who’s sold 75 million albums, just signed a $50 million endorsement deal with Pepsi (her flawless visage will festoon actual cans of soda), and will soon embark on a world tour to promote her fifth solo album, as yet untitled, due out as early as April. Who wouldn’t want to know how she gets the job done?

“I worked so hard during my childhood to meet this goal: By the time I was 30 years old, I could do what I want,” she says. “I’ve reached that. I feel very fortunate to be in that position. But I’ve sacrificed a lot of things, and I’ve worked harder than probably anyone I know, at least in the music industry. So I just have to remind myself that I deserve it.”

Anytime she wants to remind herself of all that work—or almost anything else that’s ever happened in her life—all she has to do is walk down the hall. There, across from the narrow conference room in which you are interviewing her, is another long, narrow room that contains the official Beyoncé archive, a temperature-controlled digital-storage facility that contains virtually every existing photograph of her, starting with the very first frames taken of Destiny’s Child, the ’90s girl group she once fronted; every interview she’s ever done; every video of every show she’s ever performed; every diary entry she’s ever recorded while looking into the unblinking eye of her laptop.

“Stop pretending that I have it all together,” she tells herself in a particularly revealing video clip, looking straight into the camera. “If I’m scared, be scared, allow it, release it, move on. I think I need to go listen to ‘Make Love to Me’ and make love to my husband.”

Beyoncé’s inner sanctum also contains thousands of hours of private footage, compiled by a “visual director” Beyoncé employs who has shot practically her every waking moment, up to sixteen hours a day, since 2005. In this footage, Beyoncé wears her hair up, down, with bangs, and without. In full makeup and makeup-free, she can be found shaking her famous ass onstage, lounging in her dressing room, singing Coldplay’s “Yellow” to Jay-Z over an intimate dinner, and rolling over sleepy-eyed in bed. This digital database, modeled loosely on NBC’s library, is a work in progress—the labeling, date-stamping, and cross-referencing has been under way for two years, and it’ll be several months before that process is complete. But already, blinking lights signal that the product that is Beyoncé is safe and sound and ready to be summoned— and monetized—at the push of a button.

And this room—she calls it her “crazy archive”—is a key part of that, she will explain, so, “you know, I can always say, ‘I want that interview I did for GQ,‘ and we can find it.” And indeed, she will be able to find it, because the room in which you are sitting is rigged with a camera and microphone that is capturing not just her every utterance but yours as well. These are the ground rules: Before you get to see Beyoncé, you must first agree to live forever in her archive, too.

It stands to reason that when a girl owns her every likeness, as Beyoncé does, it can make her even more determined to be perfect. (Beyoncé isn’t just selling Beyoncé’s music, of course; she’s selling her iconic stature: a careful melding of the aspirational and the unattainable.) So when she’s on tour, every night she heads back to her hotel room with a DVD of the show she’s just performed. Before going to sleep, she watches that show, critiquing herself, her dancers, her cameramen. The next morning, everyone receives pages of notes.”One of the reasons I connect to the Super Bowl is that I approach my shows like an athlete,” she says now. “You know how they sit down and watch whoever they’re going to play and study themselves? That’s how I treat this. I watch my performances, and I wish I could just enjoy them, but I see the light that was late. I see, ‘Oh God, that hair did not work.’ Or ‘I should never do that again.’ I try to perfect myself. I want to grow, and I’m always eager for new information.”She loves being onstage, she says, because it is the one time her inner critic goes silent. “I love my job, but it’s more than that: I need it,” she says. “Because before I gave birth, it was the only time in my life, all throughout my life, that I was lost.” She means this in a good way: When her brain turns off, it is, frankly, a relief. After drilling herself, repeating every move so many times, locking them in, she can then afford not to think. “It’s like a blackout. When I’m onstage, I don’t know what the crap happens. I am gone.”

Solange, Beyoncé’s little sister (and an increasingly famous singer in her own right), says it has always been this way: “I have very, very early-on memories of her rehearsing on her own in her room. I specifically remember her taking a line out of a song or a routine and just doing it over and over and over again until it was perfect and it was strong. At age 10, when everybody else was ready to say, ‘Okay, I’m tired, let’s take a break,’ she wanted to continue—to ace it and overcome it.”

It’s hard to believe it, given what Beyoncé grew up to be, but as a girl she was shy. These days, she says that Sasha Fierce, the lusty alter ego—part smolder, part fury—that she invented in her first solo video (2003’s “Crazy in Love”) to coax herself out of her own shell, has been fully integrated into her personality. Part girl next door, part mistress of the universe, Beyoncé now exudes a hip-thrusting sensuality that can be a little…intimidating. She’s hot, no doubt, but her eminence, her independence, and her ambition make some label her cool to the touch. Her allure lies in the crux of that tension—on the meridian between wanting her unabashedly curvaceous body and knowing that she’s probably right when she says, to borrow from her song “Bootylicious,” that you really aren’t ready for all that jelly.

Back in the day, the thing that made her fiercest was protecting her younger sibling. Solange recalls how Beyoncé defended her when they were teens. “I can’t tell you how many times in junior high school, how many boys and girls can say Beyoncé came and threatened to put some hands on them if they bothered me,” Solange says with a laugh. Beyoncé says she harnessed that same temper to bolster her nerve and fuel her work. “I used to like when people made me mad,” she says in the HBO documentary, remembering her suburban Texas childhood, which was shaped (some would say cut short) by her determination to be a star. “I’m like, ‘Please piss me off before the performance.’ I used to use everything.” As Jay-Z rapped of Beyoncé at the beginning of her 2006 hit “Déjà Vu,” “She about to steam. Stand back.”

“You know, equality is a myth, and for some reason, everyone accepts the fact that women don’t make as much money as men do. I don’t understand that. Why do we have to take a backseat?” she says in her film, which begins with her 2011 decision to sever her business relationship with her father. “I truly believe that women should be financially independent from their men. And let’s face it, money gives men the power to run the show. It gives men the power to define value. They define what’s sexy. And men define what’s feminine. It’s ridiculous.”

Now she says, “You know, when I was writing the Destiny’s Child songs, it was a big thing to be that young and taking control. And the label at the time didn’t know that we were going to be that successful, so they gave us all control. And I got used to it. It is my goal in life to be that example. And I think it will, hopefully, trickle down, and more artists will see that. Because it only makes sense. It’s only fair.”

There ain’t no use being hot as fish grease, she seems to understand, if someone else wields the spatula and holds the keys to the cash register. But if you can harness your own power and put it to your own use? Well, then there are no limits. That’s what the video camera is all about: owning your own brand, your own face, your own body. Only then, to borrow another Beyoncé lyric, can girls rule the world. And make no mistake, fellas: Queen Bey is comfortable on her throne.

“I now know that, yes, I am powerful,” she says. “I’m more powerful than my mind can even digest and understand.”

But Wait, What About Her Music? A few words from Beyoncé on her upcoming album, for which she’s already recorded about fifty songs.—A.W

On her collaborators: “I’ve been working with Pharrell and Timbaland and Justin Timberlake and Dream. We all started in the ’90s, when R&B was the most important genre, and we all kind of want that back: the feeling that music gave us.”

On songwriting: “I used to start with lyrics and then I’d find tracks—often it was something I had in my head, and it just so happened to go with the melody. Now I write with other writers. It starts with the title or the concept of what I’m trying to say, and then I’ll go into the booth and sing my idea. Then we work together to layer on.”

On the album’s influences: “Mostly R&B. I always have my Prince and rock/soul influences. There’s a bit of D’Angelo, some ’60s doo-wop. And Aretha and Diana Ross.”

On her inspirations: “Even the silliest little thing that you hear on the radio, it comes from something deeper. ‘Bootylicious’ was funny, but it came from people saying that I had gained weight and me being like, ‘I’m a southern woman, and this is how southern women are.’ My motivation is always to express something or to heal from something or to laugh and rejoice about something.”

Amy Wallace is a GQ correspondent.